My earliest (as far as I can recollect) mystical experience came to me at Camp Joy Bible Camp in rural Minnesota.

It was the custom their to have a campfire the final evening. It was a sacred fire of the fundamentalist sort; between songs, campers were encouraged to share “testimonies.” The testifier would walk up to the center of the group, right in front of the fire, and then tell a story about how their life had been changed by God. When they were done sharing, they would pick out a stick from an old cardboard box and throw it into the fire. It was a little ritual meant to express that whatever was just shared is being offered up to God.

On this particular summer evening, most of the stories were depressing. Everyone shared melancholy stories of death and disappointment, of loss and regret. Several campers spoke of the passing of a grandparent. One told about how their father used to beat him so he and his mother had to move away. Some told less-intense stories about the death of a pet or the ending of a relationship. A few went into unnecessarily vivid detail about past sins from which Jesus had delivered them.

As I listened, I felt mostly irritated. Many of the stories felt, to me at the time, attention-seeking. Or “much ado about nothing.” As a good stoically conservative white rural Minnesotan, I felt that drawing attention to one’s self (or being overly dramatic about adversity) was wrong somehow.

As I sat in irritation, watching the firelight flickering on the teary faces of teen testifiers, I suddenly felt overwhelmed with feelings I had never felt before. It was like pain or sorrow or grief or lament, but much heavier and darker. At the same time, unlike most experiences of pain or sorrow or grief or lament, it didn’t feel lonely. Not exactly. This deep feeling came with a strong sensation of Presence.

It was as though the pain of the other campers was my own pain, but even more than that, it was as though the pain of the world was my pain.

I felt swallowed in darkness. And then it was like a voice¹ came to me and said: “You are the suffering of the world.” Nothing in my life prepared me for that moment. It wasn’t simple empathy. It was a mystical experience of global suffering. I was feeling the woundedness of the world.

I went to my cabin early that night, sobbing with a sorrow rooted in compassion. I fell asleep crying.

The next morning, I woke up and everything felt more alive. Colors seemed richer. I felt awakened to something. But I also felt the continued presence of spiritual sorrow. It has never left.

I’d like to say I suddenly became an amazing and caring human being, some sort of precocious saint. But that isn’t really how spirituality works, at least not for me. However, something significant happened that day. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that the rest of my life has been tangled up in understanding just what that happening means.

* * * * *

My soul is wrapped up in the suffering of the world. That’s where my passion for justice comes from. And it is where the best of me is rooted.

Because of this, liberation theology isn’t just something that makes sense to me. It is something I feel, deep at the center of who I am.

Liberation theologians remind us that God dwells among those who suffer. Not just in the way God is present to everyone else, but in a special way.

God dwells with the oppressed, not because suffering is sacred or redemptive, but because God is compassionate. God draws near to those in pain, those experiencing alienation.

It is a mistake to confuse the compassion of God with the sacredness of suffering. This mistake has plagued us for as long as Christianity has been a thing.

If there were no suffering, would God draw near at all? No, because a world without suffering is a world free from alienation.

God dwells with the afflicted because they are the ones most able to name the violence and oppressions of the world for what they are. God lives with the oppressed so that the oppressed might lead us to a world free from alienation. And that is what is sacred.

Deep spirituality and faithful action require that we work in solidarity with the oppressed. Solidarity must be our sacrament, in the fullest sense of that word.

I often fail to act in solidarity. I’m loaded with insecurities and awkwardness. And my temperament and mental health can often hold me back from bold or loving action. Nevertheless, not a day of my life goes by where I’m not at some level conscious of the brokenness of the world, and the thick, lingering presence of suffering. It isn’t just that I notice it around me. Even now, I feel a connection to suffering. A sort of spiritual empathy that is always with me. And, because of this, there is a strange way in which I’m always aware of the presence of God.

You’d think this sustained experience of God’s presence would be great. It really isn’t. It isn’t as though God is always talking to me. Or giving me comfort. While I have certainly experience comfort and joy and happiness in my spirituality, the baseline for me is a rich sorrow. It isn’t mere depression, which feels empty and alienating. It is a spiritual sorrow that is full and connected. But it isn’t fun.

Every time I settle in and give my attention to the Spirit, I feel a slight weight. I feel a sense of sadness and beauty. I feel compassion.

Compassion means “to suffer together”. If you aren’t feeling the weight of it, it isn’t compassion. It is likely condescension or charity or about your own positive self-regard.

Compassion usually feels like an unhelpful burden; I don’t know what to do with it. Compassion isn’t simply a sentiment; it moves us to solidarity. Simply feeling compassion without acting in solidarity (which doesn’t have to look like participating in marches or burning down police precincts, though it certainly can) is like faith without works. It is a dead thing.

Interestingly, some of those who like to talk about Christian mysticism and contemplation and spirituality view it in a much more sunshiny way. I don’t want to discount the way many experience the Spirit as source of deep comfort and joy, not at all. But where people with a white middle class consciousness over-emphasize positive traits in their spirituality, solidarity suffers. Often, that sort of approach is just a thinly veiled worship of Whiteness. It is the spirituality of the colonizer.

One of the criticisms I often hear is that this way of framing spirituality plays into an “us versus them” mentality. As though insisting upon a spirituality of solidarity with the oppressed runs the risk of needlessly vilifying the not-oppressed. That naming “white middle class consciousness” or “spirituality of the colonizer” is needlessly divisive, dualistic, and angrily ineffective.

In Ephesians, it says “For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.”

As soon as I first encountered the work of folks like William Stringfellow or Walter Wink, this passage began to unfold in my consciousness. It makes complete sense to me that oppression is, first and foremost, a systemic problem.

The insight that the Powers are socio-spiritual forces…institutions and systems that bend towards death and oppression…rings true with my experience (both typical and mystical). And while I believe that individuals can be horrifically twisted into doing willful evil, I believe that even the biggest perpetrators of oppression are, in their own way, ensnared within the same diabolical systems as those they oppress. Their souls are malformed by their role in the system and, because of this, I believe they too experience a sort of suffering and alienation.

This is why, even though I’ve engaged in all sorts of resistance actions and despise the way in which the affluent and the powerful show up in the world, I don’t know if I could hate folks like Donald Trump or Jeff Bezos or others, even if I wanted to. All of my hate flows towards systems. I am profoundly shaped by the idea that our struggle is against the Powers, not against flesh and blood. In fact, whenever I stop and meditate about my enemies (like Trump), I feel compassion and even love.

I’m aware of how gross that may sound to some people. But I don’t think my compassionate convictions make me any less committed to acts of meaningful resistance. If anything, I argue that it makes me more committed.

My spirituality has caused me to have a heightened compassion for those who are oppressed and a strong desire to, flawed as I am, to nurture solidarity. And, in the midst of it all, even as I am increasingly aware of the flow of injustice and the nature of oppression, I am also growing in compassion for those who oppress, whether they do so willingly or are thoughtlessly acting out the role in which they find themselves.

I mean none of this in a neoliberal way. Or a Gandhian sort of way. I am not saying that we have to be nice to oppressors. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t direct anger at Trump. Or that we need to coddle the wealthy. Or any such thing. No: the rulers should be torn down from their thrones. The rich should have their wealth taken. And the oppressor should be toppled.

So this isn’t an appeal towards a sort of one-note pacifism or a claim that we can simply show gentleness and kindness to oppressors and they’ll suddenly wake up and stop being shitty.

Deep spirituality is animated by compassion and moves us to solidarity. The most compassionate thing we can do for the rich or powerful or privilege is to take those things away. This is solidarity for both the oppressed and, at the same time, compassion for the oppressor².

This is part of the clear message of Luke’s Gospel in particular. Jesus is present with the oppressed and ostracized. And when the wealthy and powerful want to experience the Kingdom of God, they are told to divest of their wealth. Even the disciples, who were neither among the destitute or the affluent, though who suffered under Roman occupation were invited to sell all of their possessions and give to the poor.

This is the great work that the Spirit places upon us: to embrace the way of compassion. A “suffering together” with God, in solidarity with the oppressed, and in resistance to the Principalities and Powers, which malform us all and breed alienation.

1. I sometimes get questions about this idea of a “divine voice.” During my teen years and early adulthood I was active in charismatic churches, where folks toss around phrases like “God told me I’m supposed to buy that house” or “I heard God say to me, ‘Randall, you need to get involved in youth ministry.’”

Though it is possible that sometimes these folks are literally hearing some sort of voice, usually such phrases function the same way as when folks say “God laid it on my heart.” It is a conviction or energizing idea. Which can be good things (though sometime not).

When I say “it was like a voice came to me” I am being metaphorical, but not simply metaphorical. It was more than a conviction or energizing idea. I didn’t “hear” a voice. However, I’ve had several mystical experiences where fully formed words come to me and they don’t feel as though I’m the one thinking them. And these words come to me sensations and feelings that are unlike anything else I’d normally ever feel. In those moments, the world becomes much bigger than it was a moment before. Everything changes, not just about my beliefs or my sense of self. But also my entire way of experiencing the world.

Even these clarifications feel too thin and inadequate. And so, instead of grappling with long and esoteric descriptions, I just go with the traditional phrasing of “it was like a voice came to me.”

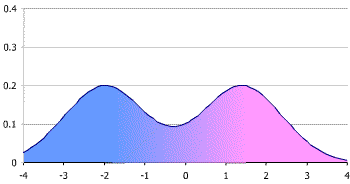

2. It may be helpful of thinking about oppressed versus oppressor in a bimodal rather than a binary way. A binary approach means that everyone is one or the other. But most of us find ourselves benefiting, at least some of the time, from the various systems of oppression.

A bimodal approach is often depicted by two overlapping bell curves, as depicted below. For example, am I among the oppressed or oppressors? I’m white, highly educated, USAmerican, a Christian minister (of sorts), etc. But I’m also transgender and neurodivergent and struggle with mental health. It is impossible to depict my “social location” with a binary understanding of oppression.

Nevertheless, we can discern in particular situations and events and systemic outcomes who is most benefiting from a particular form of oppression and who is most negatively impacted. In such cases, asking people to make a clear and decisive stand is necessary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.